This is an excerpt from The Invisible Boy Who Became Mr. Invincible which was published on Narratively in December 2019 and includes an audio version, available on Spotify.

Twelve-year-old Gilbert Alaskadi knelt on the dirt floor of his bedroom and slipped open the envelope, taking care not to tear it. He had never opened his uncle’s mail before, and he would be in for a beating if he were discovered. But something about this envelope had caught his eye: a small illustration of a herculean figure striking six men simultaneously into the air. Perhaps, he thought, this envelope contained something that could protect him.

He pulled the colorful pamphlet into his hands and scanned its contents. It was an advertisement for a bodybuilding magazine that promised readers they could be “the strongest man in the world.” Alaskadi had never heard of bodybuilding. In Chad, the north-central African country where he lived, the impoverished population had little access to the culture of fitness that was growing in popularity elsewhere in the world. But the pamphlet’s message was simple and intoxicating: Become invincible.

“I thought it was some sort of magic.” Alaskadi, now 59, says, at the bodybuilding gym he runs in London. “That is how I got into bodybuilding: I wanted to be invincible.” In the corner of the gym is a life-size cutout of Alaskadi posing proudly in a red Speedo, his gleaming, rippled physique bulging so enormously out of proportion that it appears somehow isolated from his own head. The picture was taken as he won the British Bodybuilding Championships in 2004, and Alaskadi remains imposing 15 years later. While not a tall man, his chest protrudes beyond his chin, and his biceps inflate his shirt like air in a balloon. Yet he speaks with a gentle voice and walks slowly now, with the aid of a crutch — the result of four knee replacement surgeries, kidney failure, and a major back operation.

In the nearly five decades since Alaskadi laid eyes on the pamphlet that promised him invincibility, he has overcome an array of Goliath-like obstacles: forced servitude; imprisonment; separation from loved ones; and the reality of losing everything, again and again. But for a time, he seemed truly invincible.

Alaskadi’s saga begins at the age of 10, when his father, an important elder in their remote village in southern Chad, was murdered. His mother was unable to cope with raising five children alone and sent him to live with his uncle’s family in the nearby city of Moundou. Alaskadi was immediately set to work filling in the marshland that surrounded their home. Whenever he wasn’t at school, he was forced to toil. He was last to eat and wasn’t even allowed to sit at the table. If he stepped out of line, his uncle beat him. At school, he struggled with exams and was bullied for his unwashed clothes and slight physique.

After a failed attempt to run away at the age of 11, he was beaten nearly to death. For another five years, he saw no way out, fearful of attempting another escape. Finally, he was left with no choice. One day, deep in the bush, his uncle’s truck failed to start. He told Alaskadi to climb underneath and search for the problem. Without warning, the engine started and the truck accelerated forward. “The wheel missed my head by inches,” he recalls. He knew it was no accident; his uncle wanted him dead before he got old enough to fight back.

“The wheel missed my head by inches”

Soon after, he waited until everyone was asleep and slipped into his uncle’s bedroom. He reached into the man’s jacket, which was hanging on a chair, and pulled out a handful of bills. In Alaskadi’s bag were a few clothes and the bodybuilding brochure he had kept since discovering it on his bedroom floor, neatly folded into a Bible, four years earlier. He hitchhiked his way out of the country, selling his spare clothes and only pair of shoes along the way. In Lagos, Nigeria, he found a job as a laborer in the compound of a British family, the Whites. Now 17, with his own money and a roof over his head, he was finally able to turn his attention to the sport he was convinced would be his savior: bodybuilding.

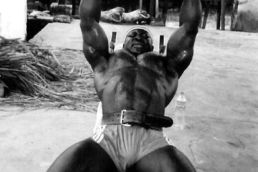

He created DIY dumbbells from concrete, although he had no idea how much they weighed until he could stand on a scale with them. He welded together a bench, and the small patio outside his room now looked somewhat like the gyms in his bodybuilding magazines. Armed with the knowledge of some basic exercises, he spent every spare minute training. His quest for invincibility had begun.

Alaskadi’s new life was taking shape, but he missed the family members he had abandoned so suddenly: his mother, siblings and cousins who lived in Moundou and the surrounding villages. Returning, even for a short time, would mean facing his uncle, but he could no longer let that stop him. A few months before he went home, he sent his uncle a letter stating that he held no resentment toward him and wasn’t seeking revenge for his maltreatment.

But returning to Chad was dangerous for other reasons. It was 1979 and the country’s long-running civil war had spiraled out of control. The Christian south and Muslim north had been fighting for years, and the French colonialists had realized that reconciliation was impossible and withdrawn. In the power vacuum, rebel groups were fighting amongst themselves, reducing the capital, N’Djamena, to rubble and forcing tens of thousands of civilians to flee south to Moundou.

One of those fleeing with her family was 13-year-old Damarese Nayo. When the bombs had started falling near her home, her father had told her and her siblings not to leave their compound. “Everyone was so scared,” she says. Soon snipers began firing indiscriminately in the city. “I was sitting under a tree at home, and a bullet hit the trunk just above my head. The next day, everybody left the city. We ran, we didn’t know where to go.”

Nayo and her family headed to the border with Nigeria, where they climbed on top of a truck bound for Moundou. Nayo sat with her family, her baby brother in her arms. As she rode, she noticed an older boy standing on the rear bumper of the truck, clinging to an exterior rail and shifting his position to avoid the fumes from the exhaust. He seemed to be staring at her, which annoyed Nayo. “I thought: Who is this guy looking at me?”

From the back of the truck, Alaskadi had recognized Nayo. “I remembered seeing her years before,” he says, “when I visited my aunt’s house in N’Djamena. She looked so nice now.” Alaskadi wanted to talk to Nayo, so he offered to hold her brother. “She just ignored me. I don’t think she liked me looking at her,” he recalls. As they disembarked, Nayo and her family melted into the crowd, and Alaskadi turned his thoughts to facing his uncle.

In order to diffuse the confrontation with his uncle, Alaskadi reverted to subservience and spent much of his time in Chad building an extension to the house. He returned to Nigeria two weeks later, exhausted but glad to have seen his family and satisfied that his uncle no longer wanted him dead.

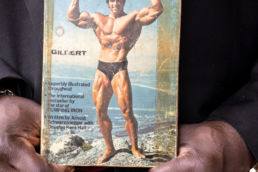

Arriving back in Lagos, Alaskadi passed a fitness shop that was proudly displaying a new book by Mr. Universe sensation Arnold Schwarzenegger in the window. A few minutes later, he emerged with a copy of Arnold: The Education of a Bodybuilder in his hands and a grin across his face.

With the help of an English-to-French dictionary, the book became Alaskadi’s training bible. By putting its lessons to use with his ever increasing array of DIY equipment, his physique exploded. Meanwhile, he gained the trust of the Whites and began working in their kitchen, alongside the family’s chef. He was so valued that they acquired him a Chadian passport — usually reserved for the wealthy and important — so that he could accompany them around the country and pass through the vast array of checkpoints without issue.

But, in 1984, Alaskadi’s life in Nigeria came to an abrupt end. The oil boom of the late ’70s had prompted millions of workers to flood in from neighboring countries, generating resentment and unrest among local Nigerians, who were suffering from high unemployment. The government decided to expel everyone in the country without a work visa, of which Alaskadi was one.

The 30-hour bus ride back to Moundou was arduous. There was a stale stench of body odor in the air as the bus pulled up to the final checkpoint at the edge of the city. Alaskadi, now 24, had spent most of the journey thinking about building a new gym for himself once back in Chad, since he had been forced to leave his equipment in Nigeria. Perhaps he could use his encyclopedic knowledge of training to open Chad’s first bodybuilding gym.

As this thought warmed Alaskadi’s imagination, a government soldier boarded the bus to check passengers’ identification. He moved from row to row, the barrel of his AK-47 rifle bouncing gently off the padded seat backs. Alaskadi was unaware that Libya — Chad’s northern neighbor, then led by Muammar Gaddafi — wanted to seize control of the oil fields near the desert border. Libya had been accused of sending antigovernment mercenaries into Moundou to stoke tensions: mercenaries with bulging muscles and immaculate documentation.

The soldier glared at Alaskadi’s passport. “Why do you have this?” he asked, his eyes coming to rest on Alaskadi’s bulging arms. Alaskadi explained that his employers had given it to him, but the soldier was unconvinced. Nobody else had a passport. Nobody else looked like they could lift the bus with their bare hands. “I am keeping it; the police commissioner will need to stamp it,” the soldier declared. “Collect it from his office tomorrow.”

The police commissioner’s office was a wide, three-story bare concrete building next to the river. Under the watchful eye of a guard, Alaskadi crossed the dusty courtyard. He was led through a corridor and into a large room with no windows, where a man in high-ranking military uniform sat behind a mahogany desk. In his hand was Alaskadi’s passport. His gaze rose slowly, and he spoke in a soft, intimidating tone. “And who are you?”

Alaskadi responded timidly: “Gilbert Alaskadi, sir.”

“I know your name. But who are you?” the commissioner demanded.

“I was living in Nigeria, sir, I am from Moundou.”

“Who do you work for?” The man narrowed his stare as though attempting to read Alaskadi’s thoughts. “Who gave you this passport?”

“I was working for Europeans in Nigeria, they gave me the passport,” Alaskadi explained.

“You are here to fight against us, aren’t you?!” the commissioner snapped.

“I don’t know anything about that, sir,” Alaskadi said, as the terrifying realization of what was happening arrived, with a cold sweat in tow. “I am an athlete, perhaps I will travel to Europe one day, so I need my passport. Please,” he offered, desperately.

“Oh, you travel to Europe too?” The commissioner said, a sarcastic grin across his face. “Sit down!” he ordered.

Alaskadi lowered himself into the chair and pulled a bundle of bills from his pocket. He held it out across the desk. In Chad, this was how difficult situations were often resolved.

The commissioner’s hand swung through the air, colliding with Alaskadi’s outstretched arm, sending the cash flying across the desk. He stood up, furious. “You think I am like those soldiers on the street?” he yelled, pulling a revolver from under the desk. “Say one more word and I’ll kill you right here.” The barrel rested a few inches from Alaskadi’s chest. “I’m sending you to N’Djamena. You can tell it to them.”

Alaskadi remains convinced that the only reason he wasn’t killed immediately was that they thought he had information. He was taken to a small holding cell at the back of the compound, ready to be transported to the capital. What happened to prisoners in the capital was common knowledge. “They hung captives from a meat hook to get information from them,” Alaskadi says with a wince. “Then a machine slowly chopped them into pieces while they were still alive. Imagine. Then they take the pieces to the mincer and throw what comes out into the river.” Many have since recounted how, during the years of war in Chad, the capital’s river regularly ran red.

The dirt floor of the tiny holding cell was damp and the smell of stale urine filled the air. The cage encircling it was rusty and misshapen, though not enough to be ineffective. In the corner, another figure lay silent. Outside, two guards with rifles sat on crooked stools. The atmosphere of grim despair was suffocating.

Late in the night, the guards yanked the door open and dragged the silent man from the cell. They beat him, tied his hands and feet together, and placed him in a large sack before carrying him out in the direction of the river bank. Alaskadi knew it would be his turn next. He told himself: “Gilbert, time to fight for your life.”

When the larger of the two guards left his stool, Alaskadi saw his opportunity. The remaining guard was tall but slight and held a long rifle that was impractical for short-range combat. Alaskadi knew he could overpower him if only he could get out of the cell. He begged the guard to let him relieve himself outside. “Please, I am not an animal. You have a gun, what am I going to do?” he said.

The guard stared at Alaskadi. “Try anything and I’ll kill you,” he said. “Turn around and put your arms up.” He opened the cage and led Alaskadi toward the riverbank, the butt of his rifle in the small of Alaskadi’s back.

Alaskadi’s hand swept around so quickly that he surprised himself. It wrapped itself around the barrel of the rifle while his other hand pulled its strap tightly around the guard’s neck. Within seconds Alaskadi’s immense frame had swallowed the man in an all-encompassing bear hug. He carried him a few feet over to the crest of the riverbank, which, owing to it being dry season, offered a steep slope down to the water. In a single motion, he threw the guard and his gun into the darkness, then scrambled down the slope. He ran along the side of the water, resisting the temptation to look back to discover the man’s fate, guessing that “he was probably hurt, but not dead.”

He reached the wide, dusty bridge that marked the southern edge of the city and clambered up to the road. A truck with a local plate approached, its lights briefly blinding Alaskadi as he stretched out his arm. The vehicle slowed and he pulled himself up to the cab, relieved to see a member of Alaskadi’s own tribe — recognizable by his skin color and facial features — at the wheel.

“Where are you going?” the man asked. “As far as you can take me.” Alaskadi replied. He slipped into the passenger seat and, with a clatter, the truck heaved itself into the darkness, toward the border with Cameroon.