Dreams of a Life

This article was originally published in The New Arab as The Migrants Risking Everything to Escape Greece in August 2020.

Dozens of lorries sit lifeless on the tarmac of Greece’s second largest port in the city of Patras. It’s a warm, bright afternoon and like any other day, the drivers wait to roll their vehicles onto the towering ship that will take them across the Mediterranean to southern Italy. Looking on from the roof of an abandoned factory nearby are six Afghan migrants. They are in Patras for one reason: to reach Italian soil by hiding aboard one of the lorries, an activity they call ‘The Game’.

Suddenly a group of drivers point and shout as they spot two of the men scaling the port’s double-walled barrier, dressed all in black with water bottles slung tightly around their torsos by a shoelace. The men sprint across the open compound and vanish into the maze of vehicles, desperately searching for a place to stow themselves; above an axle, in an engine bay, or among a trailer’s haul. A good hiding place will mean the difference between reaching Italy and ending up in a Patras jail cell.

Within minutes, a police car is speeding along the tarmac, siren blaring. The men bolt from their cover, launching themselves back over the barrier as swiftly and elegantly as gymnasts. They cross the six-lane highway that separates the port from the factory and disappear into the sprawling complex, where they will remain until their next attempt.

In late 2019, there were approximately 100 migrants in Patras, a port city 200km west of Athens. They were all young men and boys between the ages of 13 and 35, desperate to escape Greece’s immigration quagmire, with its dangerously overcrowded refugee camps and asylum interviews that take years to materialise. Their goal is to reach western Europe, where they hope to be able to build a new life.

In recent years the EU has increased pressure on Athens to ensure migrants remain in the country, making getting out of Greece incredibly difficult. Beyond boarding a ship from Patras’, there is only the treacherous route via the Balkan states, with their harsh winters and unchecked police brutality.

Patras’ “game” offers a simpler equation: a port, a handful of ships, and a few hundred lorries on which to hide. Yet, it is still gruelling: the men must endure months of squalor and intimidation living in squats controlled by people smugglers and risk severe injury evading police. For those resilient enough, success will eventually arrive, until which time a handful of volunteers, supported by the local government, provide essential support.

While the coronavirus pandemic and Greece’s resulting lockdown slowed the flow of migrants into and out of Patras, it has done little to change the underlying forces driving them. With Greece’s response to migrants becoming increasingly hostile and Europe’s attention focused on the biggest economic shock in living memory, the future for those playing Patras’ grim game seems more uncertain than ever.

It’s lunchtime at the paper mill, the largest of the derelict factories where migrants in Patras live. Sunlight decorates the yard with angular shadows. Clothes hang drying on a fence above a faucet that feeds two makeshift showers. A rusting fuse box powers a multi-socket adapter spawning a tangle of smart-phone chargers.

Dozens of men cluster in the yard to meet volunteers from NoName Kitchen. The Spanish charity is one of two organisations working directly with migrants in the city, providing food, cooking equipment, and basic medical care. On a grubby, threadbare sofa, 13-year-old Samin* winces as Anna Planas, NoName’s volunteer doctor, cleans a deep infected gash on his leg where he says a policeman kicked him.

Further into the yard, an arch leads into the paper mill’s vast hall. Piles of rubble and trash decorate the dusty concrete floor, illuminated through high, broken windows. Forty feet in the air is a great rusting crane, its platform decorated by a multi-coloured patchwork of bedding. Accessed by a narrow ledge that runs the hall’s length, the platform is one place the police deem too risky to tread. “We sleep there,” says 16-year-old Mohammed*, “otherwise the police arrest us at night.”

Upstairs, one room has been cleared of rubble to create a makeshift kitchen. A camping stove heats a large pan, next to which Omid Afzahl, a bright 24-year-old Afghan, dices tomatoes into a carrier bag. A politics graduate, he says he worked for the US-led administration in Kabul, but fled after the Taliban killed his wife and two young children when he refused to provide them with information.

He says he sees no future for himself in Greece. “I can’t work here until I receive my [Greek] ID. I’ve been waiting two years for my interview. If I fail, they will deport me back to Afghanistan. I have to leave, my life depends on it.”

Soon the smell of simmering Afghan curry fills the room. A group of men sit on a collection of disfigured seating placed around a low table. They pass around a sack of stale bread as the pot – brimming with tomatoes, spices, and egg – is placed into the centre of the excited group and quickly disappears under a tangle of hands, dipping bread into the steaming concoction.

Suddenly there is a shout of “police” from outside. The room explodes with energy as the men leap up, sending furniture tumbling. Afzhal launches himself off a stool towards a high window, grasping just enough of the ledge to pull himself up and disappear through the narrow opening. In the blink of an eye the room is deserted.

A policeman enters hurriedly, disappointed to find the room empty. “It is very difficult,” he says, with a hint of shame. “I take my orders from Athens. If we don’t stop them, [the government] fine us. I have no problem with these kids, but this uniform feeds my family.”

The police raid the factories multiple times a day, and while some officers may be uncomfortable with orders sent from Athens’ centre-right government, volunteers from NoName Kitchen report regular aggression. “If they don’t catch anybody,” Alex Sanchez, a 23-year-old volunteer says, “they spoil food and break personal items.”

” There’s no efficient smuggling operation without corrupt officials. Whether it’s police, port officials, or anyone in a position of power”

Patras’ migrants are in a precarious legal position. The majority are registered asylum-seekers awaiting their immigration interview, but this can take years. While travel within the country is permitted, Patras is out of bounds and the police have the power to arrest and “remove” migrants caught in the city.

Those captured are held in jail cells until they can be transported to Athens where they are offloaded onto a street corner. Usually, after sleeping rough for a night, they catch a coach back to Patras. When asking after a migrant who had disappeared from the factories, the most common response was: “the police took him,” followed by, “he’ll be back tomorrow.”

Nikos Papageorgio is a leading figure at the local human rights charity, Kinesis. He says the police torment is a preventative measure, “to force migrants to accept Patras is out of bounds, and that there is no sympathy for them here.” Papageorgio is adamant that migrants in Patras should be treated as refugees. “Their condition,” he tells The New Arab, “has been dictated by the destructive policies of the West, which has devastated their countries”.

The problem, Papageorgio continues, is compounded by an underfunded asylum process. “The refugee framework in Greece,” he says, “is operating under inhumane, undignified conditions. This feeds into the hands of smugglers who control the migration process almost everywhere in Greece.”

Indeed, ‘The Game’ in Patras is controlled by Afghan smuggling gangs who charge $1,200 to stay in the factories. Anyone unwilling or unable to pay is removed using intimidation and violence. The smugglers’ “agents,” who live in the squats 24/7 prevent non-paying migrants from approaching the port. “If we don’t pay,” says Mohammed*, “we can’t play The Game. They take your belongings and beat you.”

The Afghan smuggling network is a vast and interconnected operation. By exploiting corruption in host countries, they are able to profit from migrants at every stage of their journey. “There’s no efficient smuggling operation without corrupt officials,” says Papageorgio, “whether it’s police, port officials, or anyone in a position of power.”

As a result, almost all the migrants in Patras have already paid the smugglers thousands of dollars to get this far. The silver lining is that their interests are aligned: the money is held by an intermediary – a business or trusted middleman – and only released to the smugglers once the men reach their destination.

Many migrants use savings or take out loans to pay, while others receive money from relatives and friends abroad. “My family in Afghanistan sends me a little money,” says Jawad Aziz, a 24-year-old electrician from Kabul, “but they don’t have much, my father earns one euro per day.”

Elsewhere in Greece migrants can find work illegally, but Aziz says his friends worked for three months on a farm and were never paid. “The Greek boss refused, they didn’t even get money for the train! You see why we have to go?”

The need for money is low however, since the men rarely leave the factory other than to attempt The Game. Crime among them is rare. “I never heard of any problems.” says Maria, who runs a small cafe close to the paper mill. “They never broke into anywhere or stole anything.”

Many migrants use savings or take out loans to pay, while others receive money from relatives and friends abroad. “My family in Afghanistan sends me a little money,” says Jawad Aziz, a 24-year-old electrician from Kabul, “but they don’t have much, my father earns one euro per day.”

Elsewhere in Greece migrants can find work illegally, but Aziz says his friends worked for three months on a farm and were never paid. “The Greek boss refused, they didn’t even get money for the train! You see why we have to go?”

The need for money is low however, since the men rarely leave the factory other than to attempt The Game. Crime among them is rare. “I never heard of any problems.” says Maria, who runs a small cafe close to the paper mill. “They never broke into anywhere or stole anything.”

On the exterior wall of the cemetery, graffiti reads “foreigners out of Greece,” a reminder that even in Patras, Greece’s most left-wing city, some remain staunchly opposed to the migrants’ presence.

Nevertheless, Bruno Alverez, director of NoName Kitchen, describes the city as “a little island of hope in the middle of a nightmare.” In Bosnia and Serbia, where the charity also operates, Alverez tells of aggressive hostility from local government and residents alike. “In Patras, when we go to the markets and bakeries, they give us food. We feel extremely well supported.”

This local support has allowed Kinisis and NoName, with the backing of the mayor’s office, to alleviate the worst of the conditions in the factories, installing running water and showers, and delivering hot meals for the migrants three times per week.

Despite this, Patras’ mayor, Konstantinos Peletidis, is irreverent about solutions. “It’s not about better food or accommodation,” he says. “These people wish to join their families or just get a job and build a normal life.”

Peletidis echoes Papageorgio’s view that the policies of the West are responsible for the problems Greece faces. “When there is military intervention somewhere, six months later there are refugees in Patras. It is the responsibility of the aggressors to support these people, but instead, thanks to EU legislation, Greece has become the guard dogs of Europe.”

Because the smugglers in Patras are Afghan, other ethnicities know to stay away from the city. For the Afghans in the factories, this is seen as a good thing: ethnic clashes are commonplace in Greece’s overcrowded camps and most of them feel safer among their fellow countrymen. “It would be chaos otherwise,” says Afzhal.

One of the unaccompanied minors, 16-year-old Mohammed Husseni, shows me a large scar on his head. He says before he came to Patras he was a victim of an ethnic attack in the overcrowded Moria camp on the Greek island of Lesbos. “It was worse than Afghanistan,” he says, “groups fighting religious and ethnic wars. Three men attacked me, I needed 10 stitches. At least here nobody is trying to kill you.”

Yet, The Game comes at great physical risk to those who play it. While all will suffer cuts and bruises living day-to-day, an unlucky few will wind up in hospital. Hasan*, a quiet 19-year-old, was hit by a car while running from police. “He went pheeeeeeeeew!” his friend explained, while drawing a large arc with his hand to illustrate a body flying through the air. He was taken to hospital by ambulance after suffering a broken arm and a head injury that required stitches.

In a suburban cemetery on the outskirts of the city, two headstones marked only by the numbers “438” and “427” offer a grim reminder that The Game can, occasionally, be fatal. The graves are of two Kurdish migrants who perished in a fire, along with 11 others, aboard a ship crossing to Italy in 1997. “We tried to reach out to embassies to identify them,” says a cemetery administrator, “but we never heard back.”

As Greece went into coronavirus lockdown in mid-March, the number of ships leaving the port fell sharply and The Game ground to a halt, meanwhile the police stepped back too. “The restrictions didn’t have a big impact” says Alex Sawizki, the NoName volunteer working in Patras at that time, “these guys were always in a form of lockdown.”

In late May, as the restrictions were lifted, lots of the men suddenly made it to Italy and new migrants began to arrive once more. At the same time the police returned in force. “From one day to the next,” says Sawizki, “there were a lot of police beatings, really aggressive behaviour.”

As the EU turns its attention to repairing the damage wrought by the pandemic, Greece may find its methods of controlling migrants under less scrutiny. In December, Amnesty International damned the rise in police violence across the country as “extremely worrying”, describing the sharp rise in incidents as indicative of systemic problems in regards to violence and impunity within the police.

“The Game may be brutal, but for those who are willing to endure, the hope of success is not misplaced”

Despite making little progress on improving conditions for migrants, Greece is expecting 100,000 arrivals this year. Many will be desperate to move past the country’s imploding immigration system. Some will no doubt try their luck in Patras.

Since last November, all of the men The New Arab maintained contact with have reached western Europe. Afzhal is now in refugee accommodation in Switzerland awaiting his asylum interview. “It is amazing here,” he says in a text message. The Game may be brutal, but for those who are willing to endure, the hope of success is not misplaced.

The smugglers, meanwhile, seem likely to continue to profit from the desperation of others. The gang in Patras have been there for years, and the brazen way in which they operate suggests they know all too well whose pockets to line in order to ensure their operation remains unchallenged.

For now, Kinisis and NoName continue to bring small comforts to the young men in the factories. Supported by their allies in city hall, they have been able to achieve more in Patras than in other migration flashpoints across Europe, delivering something so sorely lacking in the lives of these migrants: humanity.

Sitting in the cool evening air on the roof of the paper mill watching the sun set behind the port, a mere 200 meters away, the ships appeared close enough to touch. Two of Afzhal’s friends had made it to Italy the previous night, but were being returned after Italian police discovered them.

“Imagine,” Afzhal said with a dark chuckle, “you think you’ve won, then you have to come back to this. Your heart would explode.”

Mr. Invincible

This is an excerpt from The Invisible Boy Who Became Mr. Invincible which was published on Narratively in December 2019 and includes an audio version, available on Spotify.

Twelve-year-old Gilbert Alaskadi knelt on the dirt floor of his bedroom and slipped open the envelope, taking care not to tear it. He had never opened his uncle’s mail before, and he would be in for a beating if he were discovered. But something about this envelope had caught his eye: a small illustration of a herculean figure striking six men simultaneously into the air. Perhaps, he thought, this envelope contained something that could protect him.

He pulled the colorful pamphlet into his hands and scanned its contents. It was an advertisement for a bodybuilding magazine that promised readers they could be “the strongest man in the world.” Alaskadi had never heard of bodybuilding. In Chad, the north-central African country where he lived, the impoverished population had little access to the culture of fitness that was growing in popularity elsewhere in the world. But the pamphlet’s message was simple and intoxicating: Become invincible.

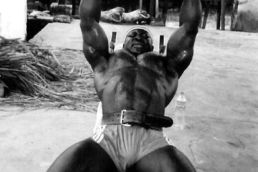

“I thought it was some sort of magic.” Alaskadi, now 59, says, at the bodybuilding gym he runs in London. “That is how I got into bodybuilding: I wanted to be invincible.” In the corner of the gym is a life-size cutout of Alaskadi posing proudly in a red Speedo, his gleaming, rippled physique bulging so enormously out of proportion that it appears somehow isolated from his own head. The picture was taken as he won the British Bodybuilding Championships in 2004, and Alaskadi remains imposing 15 years later. While not a tall man, his chest protrudes beyond his chin, and his biceps inflate his shirt like air in a balloon. Yet he speaks with a gentle voice and walks slowly now, with the aid of a crutch — the result of four knee replacement surgeries, kidney failure, and a major back operation.

In the nearly five decades since Alaskadi laid eyes on the pamphlet that promised him invincibility, he has overcome an array of Goliath-like obstacles: forced servitude; imprisonment; separation from loved ones; and the reality of losing everything, again and again. But for a time, he seemed truly invincible.

Alaskadi’s saga begins at the age of 10, when his father, an important elder in their remote village in southern Chad, was murdered. His mother was unable to cope with raising five children alone and sent him to live with his uncle’s family in the nearby city of Moundou. Alaskadi was immediately set to work filling in the marshland that surrounded their home. Whenever he wasn’t at school, he was forced to toil. He was last to eat and wasn’t even allowed to sit at the table. If he stepped out of line, his uncle beat him. At school, he struggled with exams and was bullied for his unwashed clothes and slight physique.

After a failed attempt to run away at the age of 11, he was beaten nearly to death. For another five years, he saw no way out, fearful of attempting another escape. Finally, he was left with no choice. One day, deep in the bush, his uncle’s truck failed to start. He told Alaskadi to climb underneath and search for the problem. Without warning, the engine started and the truck accelerated forward. “The wheel missed my head by inches,” he recalls. He knew it was no accident; his uncle wanted him dead before he got old enough to fight back.

“The wheel missed my head by inches”

Soon after, he waited until everyone was asleep and slipped into his uncle’s bedroom. He reached into the man’s jacket, which was hanging on a chair, and pulled out a handful of bills. In Alaskadi’s bag were a few clothes and the bodybuilding brochure he had kept since discovering it on his bedroom floor, neatly folded into a Bible, four years earlier. He hitchhiked his way out of the country, selling his spare clothes and only pair of shoes along the way. In Lagos, Nigeria, he found a job as a laborer in the compound of a British family, the Whites. Now 17, with his own money and a roof over his head, he was finally able to turn his attention to the sport he was convinced would be his savior: bodybuilding.

He created DIY dumbbells from concrete, although he had no idea how much they weighed until he could stand on a scale with them. He welded together a bench, and the small patio outside his room now looked somewhat like the gyms in his bodybuilding magazines. Armed with the knowledge of some basic exercises, he spent every spare minute training. His quest for invincibility had begun.

Alaskadi’s new life was taking shape, but he missed the family members he had abandoned so suddenly: his mother, siblings and cousins who lived in Moundou and the surrounding villages. Returning, even for a short time, would mean facing his uncle, but he could no longer let that stop him. A few months before he went home, he sent his uncle a letter stating that he held no resentment toward him and wasn’t seeking revenge for his maltreatment.

But returning to Chad was dangerous for other reasons. It was 1979 and the country’s long-running civil war had spiraled out of control. The Christian south and Muslim north had been fighting for years, and the French colonialists had realized that reconciliation was impossible and withdrawn. In the power vacuum, rebel groups were fighting amongst themselves, reducing the capital, N’Djamena, to rubble and forcing tens of thousands of civilians to flee south to Moundou.

One of those fleeing with her family was 13-year-old Damarese Nayo. When the bombs had started falling near her home, her father had told her and her siblings not to leave their compound. “Everyone was so scared,” she says. Soon snipers began firing indiscriminately in the city. “I was sitting under a tree at home, and a bullet hit the trunk just above my head. The next day, everybody left the city. We ran, we didn’t know where to go.”

Nayo and her family headed to the border with Nigeria, where they climbed on top of a truck bound for Moundou. Nayo sat with her family, her baby brother in her arms. As she rode, she noticed an older boy standing on the rear bumper of the truck, clinging to an exterior rail and shifting his position to avoid the fumes from the exhaust. He seemed to be staring at her, which annoyed Nayo. “I thought: Who is this guy looking at me?”

From the back of the truck, Alaskadi had recognized Nayo. “I remembered seeing her years before,” he says, “when I visited my aunt’s house in N’Djamena. She looked so nice now.” Alaskadi wanted to talk to Nayo, so he offered to hold her brother. “She just ignored me. I don’t think she liked me looking at her,” he recalls. As they disembarked, Nayo and her family melted into the crowd, and Alaskadi turned his thoughts to facing his uncle.

In order to diffuse the confrontation with his uncle, Alaskadi reverted to subservience and spent much of his time in Chad building an extension to the house. He returned to Nigeria two weeks later, exhausted but glad to have seen his family and satisfied that his uncle no longer wanted him dead.

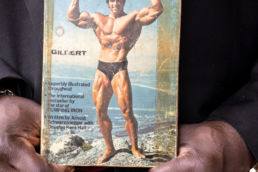

Arriving back in Lagos, Alaskadi passed a fitness shop that was proudly displaying a new book by Mr. Universe sensation Arnold Schwarzenegger in the window. A few minutes later, he emerged with a copy of Arnold: The Education of a Bodybuilder in his hands and a grin across his face.

With the help of an English-to-French dictionary, the book became Alaskadi’s training bible. By putting its lessons to use with his ever increasing array of DIY equipment, his physique exploded. Meanwhile, he gained the trust of the Whites and began working in their kitchen, alongside the family’s chef. He was so valued that they acquired him a Chadian passport — usually reserved for the wealthy and important — so that he could accompany them around the country and pass through the vast array of checkpoints without issue.

But, in 1984, Alaskadi’s life in Nigeria came to an abrupt end. The oil boom of the late ’70s had prompted millions of workers to flood in from neighboring countries, generating resentment and unrest among local Nigerians, who were suffering from high unemployment. The government decided to expel everyone in the country without a work visa, of which Alaskadi was one.

The 30-hour bus ride back to Moundou was arduous. There was a stale stench of body odor in the air as the bus pulled up to the final checkpoint at the edge of the city. Alaskadi, now 24, had spent most of the journey thinking about building a new gym for himself once back in Chad, since he had been forced to leave his equipment in Nigeria. Perhaps he could use his encyclopedic knowledge of training to open Chad’s first bodybuilding gym.

As this thought warmed Alaskadi’s imagination, a government soldier boarded the bus to check passengers’ identification. He moved from row to row, the barrel of his AK-47 rifle bouncing gently off the padded seat backs. Alaskadi was unaware that Libya — Chad’s northern neighbor, then led by Muammar Gaddafi — wanted to seize control of the oil fields near the desert border. Libya had been accused of sending antigovernment mercenaries into Moundou to stoke tensions: mercenaries with bulging muscles and immaculate documentation.

The soldier glared at Alaskadi’s passport. “Why do you have this?” he asked, his eyes coming to rest on Alaskadi’s bulging arms. Alaskadi explained that his employers had given it to him, but the soldier was unconvinced. Nobody else had a passport. Nobody else looked like they could lift the bus with their bare hands. “I am keeping it; the police commissioner will need to stamp it,” the soldier declared. “Collect it from his office tomorrow.”

The police commissioner’s office was a wide, three-story bare concrete building next to the river. Under the watchful eye of a guard, Alaskadi crossed the dusty courtyard. He was led through a corridor and into a large room with no windows, where a man in high-ranking military uniform sat behind a mahogany desk. In his hand was Alaskadi’s passport. His gaze rose slowly, and he spoke in a soft, intimidating tone. “And who are you?”

Alaskadi responded timidly: “Gilbert Alaskadi, sir.”

“I know your name. But who are you?” the commissioner demanded.

“I was living in Nigeria, sir, I am from Moundou.”

“Who do you work for?” The man narrowed his stare as though attempting to read Alaskadi’s thoughts. “Who gave you this passport?”

“I was working for Europeans in Nigeria, they gave me the passport,” Alaskadi explained.

“You are here to fight against us, aren’t you?!” the commissioner snapped.

“I don’t know anything about that, sir,” Alaskadi said, as the terrifying realization of what was happening arrived, with a cold sweat in tow. “I am an athlete, perhaps I will travel to Europe one day, so I need my passport. Please,” he offered, desperately.

“Oh, you travel to Europe too?” The commissioner said, a sarcastic grin across his face. “Sit down!” he ordered.

Alaskadi lowered himself into the chair and pulled a bundle of bills from his pocket. He held it out across the desk. In Chad, this was how difficult situations were often resolved.

The commissioner’s hand swung through the air, colliding with Alaskadi’s outstretched arm, sending the cash flying across the desk. He stood up, furious. “You think I am like those soldiers on the street?” he yelled, pulling a revolver from under the desk. “Say one more word and I’ll kill you right here.” The barrel rested a few inches from Alaskadi’s chest. “I’m sending you to N’Djamena. You can tell it to them.”

Alaskadi remains convinced that the only reason he wasn’t killed immediately was that they thought he had information. He was taken to a small holding cell at the back of the compound, ready to be transported to the capital. What happened to prisoners in the capital was common knowledge. “They hung captives from a meat hook to get information from them,” Alaskadi says with a wince. “Then a machine slowly chopped them into pieces while they were still alive. Imagine. Then they take the pieces to the mincer and throw what comes out into the river.” Many have since recounted how, during the years of war in Chad, the capital’s river regularly ran red.

The dirt floor of the tiny holding cell was damp and the smell of stale urine filled the air. The cage encircling it was rusty and misshapen, though not enough to be ineffective. In the corner, another figure lay silent. Outside, two guards with rifles sat on crooked stools. The atmosphere of grim despair was suffocating.

Late in the night, the guards yanked the door open and dragged the silent man from the cell. They beat him, tied his hands and feet together, and placed him in a large sack before carrying him out in the direction of the river bank. Alaskadi knew it would be his turn next. He told himself: “Gilbert, time to fight for your life.”

When the larger of the two guards left his stool, Alaskadi saw his opportunity. The remaining guard was tall but slight and held a long rifle that was impractical for short-range combat. Alaskadi knew he could overpower him if only he could get out of the cell. He begged the guard to let him relieve himself outside. “Please, I am not an animal. You have a gun, what am I going to do?” he said.

The guard stared at Alaskadi. “Try anything and I’ll kill you,” he said. “Turn around and put your arms up.” He opened the cage and led Alaskadi toward the riverbank, the butt of his rifle in the small of Alaskadi’s back.

Alaskadi’s hand swept around so quickly that he surprised himself. It wrapped itself around the barrel of the rifle while his other hand pulled its strap tightly around the guard’s neck. Within seconds Alaskadi’s immense frame had swallowed the man in an all-encompassing bear hug. He carried him a few feet over to the crest of the riverbank, which, owing to it being dry season, offered a steep slope down to the water. In a single motion, he threw the guard and his gun into the darkness, then scrambled down the slope. He ran along the side of the water, resisting the temptation to look back to discover the man’s fate, guessing that “he was probably hurt, but not dead.”

He reached the wide, dusty bridge that marked the southern edge of the city and clambered up to the road. A truck with a local plate approached, its lights briefly blinding Alaskadi as he stretched out his arm. The vehicle slowed and he pulled himself up to the cab, relieved to see a member of Alaskadi’s own tribe — recognizable by his skin color and facial features — at the wheel.

“Where are you going?” the man asked. “As far as you can take me.” Alaskadi replied. He slipped into the passenger seat and, with a clatter, the truck heaved itself into the darkness, toward the border with Cameroon.

Bricks and Mortar

This project was featured in The Guardian Weekend Magazine print and online, on August 3rd 2019, as well as on BBC Breakfast on the 5th of August 2019.

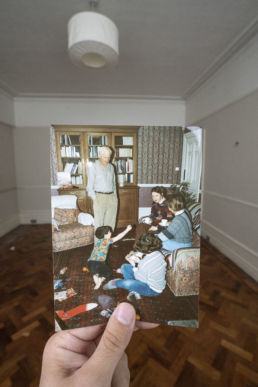

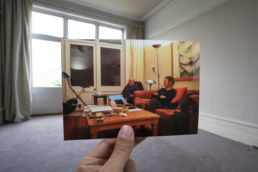

My earliest memory of our house is from the day we moved in: scrambling through the dusty cellar, my father in tow, and finding a model train that the previous owner had left behind. It was my first experience of moving home; I chose my bedroom, decided where my toys would go and was delighted to discover, as any six-year-old boy would, that the gaudy Roman bathroom tiles contained illustrations of topless ladies. These were my first glimpses of a building that would help nurture me into adulthood and, in many ways, become a fifth member of our family.

Years later my father overheard me tell a friend that I was “going home” as I set off back to university. “This is your home,” he said. He was right, of course. Just as my father remained my father even when I was not with him, the house remained my home even when I was not living in it.

The house was not only a space for family life, but also for my parents’ work as artists and printmakers. Inside their home studios, they produced pieces that would be exhibited far and wide, including etchings they printed for the likes of Lucian Freud, Frank Auerbach, and Celia Paul. The House was both deeply personal and it was our connection to the far reaches of the world through the work that was produced inside it.

Last August – 28 years after moving in – my father passed away in the living room, my sister and I beside him. The house was witness to the loss of its last residing family member; the two of us children had moved out years ago, and my mother had died in 2013 in the very same room.

Following my father’s death, we slowly dismantled the contents of our house, picking it apart piece by piece, room by room, memory by memory. Each day, it became less recognisable, less ours. Eventually, void of its contents with its bare walls exposing shadowy outlines where once a picture hung or a bookcase rested, it appeared as something it had never been: just bricks and mortar.

We fill our houses with the carefully curated paraphernalia of life. Our personalities, beliefs, wealth, health, love and occasionally even our very soul can be observed through our homes. As we grow from childhood to adolescence, teenagehood to young adult and beyond, we live out so many new experiences, play out so many childish fantasies, and resolve so much angst within those walls that they become intricately attached to our innermost selves. The thought of letting go is like tearing out a part of us, as though everything that happened inside them would vanish into the ether of forgotten memories, were we unable to return to the very spot on which they occurred.

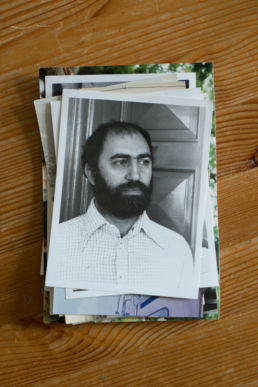

By connecting the memories held in photographs with the physical reality of the spaces in which they existed, this project attempts to uncover a portrait of our home from the relentless veil of time. In doing so, it explores the changing space that photography can occupy and its role in shaping the way we experience the world around us.

Belgrade's theatre of broken dreams

This is an excerpt from Meet the man who built Belgrade’s theatre of broken dreams, where the Yugoslav ideal lived and died which was published on The Calvert Journal in June 2019.

Ljubiša Ristić was once the daring star of Yugoslav theatre. Then the state he had dedicated his life and art to collapsed into bloodshed. This is the story of how loyalty to a political ideal ruined a cultural icon.

Among the dilapidated structures of an old industrial district in Belgrade is a crumbling, 19th-century factory. The building, once Yugoslavia’s largest sugar refinery, stands proudly even as parts of its roof succumb to gravity and its red-brick walls gently bow in sympathy. One section of the building, however, remains intact: windows glazed, roof sealed, brickwork perpendicular. In winter, a small steel chimney emits a thin trail of smoke.

In fact, this 50-metre stretch of The Sugar Factory houses a 450-seat avant-garde theatre, as well as a ballet hall, restaurant, bar, greenhouse, and a giant birdcage full of brightly-coloured parakeets. Its palatial spaces and cosy corners blend elements of an ancient temple with a Bond villain’s lair: faux-Roman columns stand by glittering Egyptian arches; murals depict characters from Eastern mythology meeting those from European classics; a grand piano rests on a marble floor under a ceiling of shimmering LED stars, next to a wall of tube televisions.

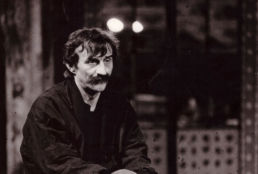

This is the eponymous home of KPGT, a theatre troupe led by enigmatic director Ljubiša Ristić. Now 72, he is energetic, articulate, and full of charisma. His presence fills the room with an air of unpretentious knowing: a man who has seen it all, remembered every detail, and continued unfazed. In the days when Belgrade was the capital of Yugoslavia, Ristić and KPGT were an international sensation. Today, the director is a controversial character in Serbia and the theatre lies mostly quiet, the restaurant’s ovens cold, the stage empty.

Ristić’s story is one of a cultural icon caught up in a destructive battle for power. His biography maps the rise and collapse of Yugoslavia itself, with all the idealism, compromise, and brutality that ultimately entailed. And, after two decades struggling to survive, there are signs that the story of this man and his theatre might not be over just yet.

Yugoslavia was birthed in the Partisan struggle against Nazi occupation, led by Josip Broz Tito. After the war, Tito united six nation states (Croatia, Slovenia, Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Macedonia), along with two autonomous regions (Vojvodina and Kosovo), into a centralised communist republic, promoting “Brotherhood and Unity” while forcefully suppressing nationalist sentiment.

Ristić’s biography maps the rise and collapse of Yugoslavia itself, with all the idealism, compromise, and brutality that ultimately entailed

As the post-war state developed into a global force, prospering in a neutral position between the Cold War superpowers, Ristić, the son of prominent wartime partisans, was growing up in Pristina, Kosovo. Taking after his parents, Ristić was politically minded and a staunch supporter of the federalism of the communist state. He joined the ruling party, the League of Communists, in 1962, aged 16. Six years later, he played a significant role in the 1968 student protest movement, opposing Titoist reforms that he felt betrayed the country’s roots. He left the party in 1971, unable to accept its continued move toward the political centre, which had seen significant powers devolved to Yugoslavia’s individual states, something Ristić feared would lead to a rise in nationalism. Away from politics, Ristić completed his degree at the Belgrade Academy of Theatre, and by the mid-70s was a rising star of stage direction.

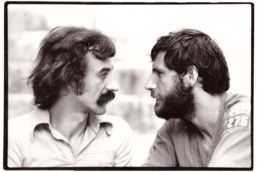

When nationalist movements indeed began to take hold across the federation, the director saw an opportunity to promote unity through culture. In 1977, he formed a theatre troupe with Croatian choreographer Nada Kokotović, Slovenian playwright Dušan Jovanović, and Croatian (now Hollywood) actor Rade Šerbedžija. Ristić says that the idea was to collect “the diversity [of Yugoslavia] in a unified cultural space, to preserve these differences which were the richness of society.” They called the troupe “KPGT” — the first letters of the words for “theatre” in four Yugoslav languages.

By the early 1980s, KPGT was a critically acclaimed company operating on the global stage. Their largest production, Carmina Burana, was seen by over 100,000 people in its first fortnight at the Belgrade Sava Centre. Meanwhile, The Liberation of Skopje — one of KPGT’s most renowned productions — would ultimately be performed over 800 times in cities throughout the world, including New York, London, and Moscow.

Contrary to other Yugoslav troupes, KPGT operated without state subsidies, both to maintain freedom of expression and because, for Ristić, ticket sales were the only valuable measure of success: while subsidies kept tickets affordable, they also reduced the appetite for creative risk. Reviewing the US premiere of The Liberation of Skopje in Denver in 1982, the American magazine Bravo positively described KPGT as an “aberration” from the routine and conventional Yugoslav productions emerging at the time.

In 1985, Ristić found KPGT a permanent home in the struggling national theatre in the city of Subotica, Vojvodina. Ristić discovered a staff comprised of bickering nationalities — a microcosm of the growing disagreements between the Yugoslav states — and began forging a unified company able to produce the kind of spectacles that soon placed the city on the cultural map. Danka Palian, a company member from Sarajevo, recalls that Ristić “impressed upon the team his belief that ‘there is one universal language, and it’s the language of theatre’.”

By the end of the 80s, Ristić was one of Yugoslavia’s most important directors, known for a pointed and experimental style that confronted the issues of the day. Festivals organised by KPGT regularly included hundreds of performers from around Yugoslavia and beyond, operating on stages located in multiple cities simultaneously.

“I was given names like ‘the father of political theatre’,” recalls Ristić. “That wasn’t true. We were not using theatre for political activism. We used political themes to tell the stories of life.”

Outside of the theatre, nationalist sentiments were escalating into sporadic violence. Tito’s death in 1980 had fractured the national psyche, and foreign powers, keen to see Yugoslavia’s influence reduced, took the opportunity to stoke division.

In 1986, Slobodan Milošević became leader of the Serbian League of Communists. In order to gain support among Serbian nationalists, he had exploited opposition to Kosovar independence. Once elected, he took control of both Kosovo and Vojvodina by revoking devolved powers, and helped his allies into power in Montenegro. This imbalance of power provided fuel for nationalist movements across the union and, in 1991, Slovenia and Croatia declared independence, triggering war. Over the next four years, the dream of a united Yugoslavia disintegrated in horrifying, bloody fashion.

While Ristić stood opposed to the violence and avoided attachment to any side, the war immediately affected KPGT. Some of the troupe, including its co-founders residing outside Serbia, became detached, and cultural sanctions imposed by the UN made it impossible to tour outside the country, decimating their budget. “We could make $1 million a year in America or Europe,” Ristić says. “Under cultural sanctions, we had no possibility to go abroad.” Unable to travel, KPGT extended their operations to Belgrade in 1994. They squatted the derelict Sugar Factory and began performing to small audiences without windows, doors, power, or water.

When the violence came to a temporary end in 1995, Milošević had recast himself as peacemaker and began promoting “unity” among what remained of the federation. Milošević‘s influential wife and confidante, Mira Marković, decided to counter growing Serbian nationalist forces — which included her husband’s Socialist Party of Serbia (SPS) — with a more traditional form of Yugoslav communism. She formed a new party, The Yugoslav Left (JUL), merging 19 smaller left-wing parties, and began searching for a charismatic leader to unite its various factions.

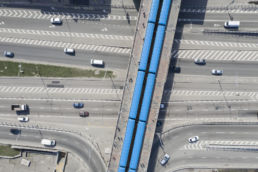

Above Left: A view of Kyiv's Left Bank from the air

Kyiv’s Left Bank – confusingly the area of the city situated to the right of the Dnieper river – is commonly derided as the lesser side of the city, thanks to its lack of landmarks, poor infrastructure, giant industrial zones, and endless rows of dilapidated Soviet-era housing projects.

Viewed from above, however, the Left Bank provides a variety of form and texture that cannot be found elsewhere in the city. As spring takes hold, the intermingling of nature and humanity turns the Left Bank into a complex concert of colour, pattern and tone.

Welcome to Comfort Town.

This is an excert from A nation’s tensions are laid bare in Kyiv’s colourful city-within-a-city. Welcome to Comfort Town which was published on The Calvert Journal in April 2019.

The election on Sunday of comedian Volodymyr Zelensky as the nation’s new president has shown just how deep dissatisfaction with the status quo runs in Ukraine. In one corner of Kyiv, a housing development tells the story of generational divisions and the uneasy search for a workable future among the country’s youth.

Glance out of the aeroplane window as you descend into Kyiv’s Borispol airport and you are likely to spot a 40-hectare explosion of rainbow-coloured concrete on the ground below. This is Comfort Town, erupting from its drab surroundings like Lego on a shabby grey carpet.

Comfort Town’s 180 low-rise apartment buildings are indeed inspired by children’s building blocks; a playful response to the sprawling 1950s and 60s communist-era housing that encircles them. The secured grounds operate as a city-within-a-city, housing everything needed for modern life, from shops and restaurants to schools and gyms.

“Your little slice of Europe in Kyiv,” declares the brochure. Indeed, for the most part, its 8,500 apartments and manicured courtyards have been embraced by a generation of young families and urban professionals who feel culturally closer to Europe than to the country’s Soviet heritage.

Ukraine is a country struggling against endemic corruption, suffocating poverty, chronic depopulation, and a gruelling war with Russia-backed separatists. Stifled by a powerful elite unwilling to relinquish control, much of the country has failed to modernise in its 28 years of independence. In this context, islands of modernity like Comfort Town raise the important question of whether such developments are a precursor to wider progress in the country, or a symptom of a system incapable of change.

Conceived in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, Comfort Town was built on the site of a disused rubber factory on Kyiv’s Left Bank. Confusingly located to the right of the Dnieper river, the Left Bank is often derided as the less desirable side of the city, thanks to its lack of landmarks, poor transport, and endless Soviet-era housing projects, now some of the most deprived neighbourhoods in the city. Despite this, Comfort Town has proven incredibly popular, claiming the title of “Ukraine’s most successful development” (in terms of unit sales) since independence.

Unlike many older estates, the buildings and common spaces in Comfort Town are well maintained. Responsibility is shared among residents through service charges, democratic voting rights, and a Facebook group with nearly 10,000 members. People take collective responsibility in a way that is uncommon elsewhere in the city.

“In the Soviet Union, people didn’t have to take responsibility, because somebody else did,” explains Alina Dvorzhanska, 30, a property manager and interior designer who works regularly in Comfort Town. She tells me it’s normal for common areas in older buildings to be uncared for. “The younger generation wants to live in new developments because the neighbourhood thinks differently. They care because they know no one else will.”

“The younger generation wants to live in new developments because the neighbourhood thinks differently.”

By isolating itself from the outside, Comfort Town has also become a refuge for some residents who have been subject to racism elsewhere. Neuro Lloyd, a black Zimbabwean who emigrated to Ukraine six years ago to study medicine, has been violently attacked in other parts of the city eight times. He receives verbal abuse on an almost almost daily basis. “In Comfort Town,” he says, “I haven’t had any of those problems. I feel so much more comfortable walking around, especially at night.”

Although beyond the reach of the city’s poorest, the complex is still considered affordable for those on middle incomes. For many residents, however, living in Comfort Town is about more than economics. Tetiana Donets, 23, a film producer who lives and works in Comfort Town, says she loves where she lives but is under no illusions about what her home represents…

Into the Zone: 4 days inside Chernobyl's secretive 'stalker' subculture

This article was originally published on The Calvert Journal as Into the zone: 4 days inside Chernobyl’s secretive ‘stalker’ subculture on January 8th 2019.

In the shadows of the tourist boom in Chernobyl Exclusion Zone are the ‘stalkers’; Young Ukrainian men, now offering an illegal alternative to the theatre of the official tours.

I can feel the undergrowth digging into my legs as the two of us hide among the trees in anxious silence. The darkness is so absolute I feel entombed within it. It’s been seven hours since my last drink. Kirill, our guide, left to get water with the others, but they haven’t returned; after hearing a barking dog in the distance, we fear they’ve been caught.

We entered the 2,600-square kilometre Chernobyl Exclusion Zone illegally last night. Without Kirill, we are lost, somewhere in a forest, with no water, no map, and no plan.

In recent years, the Zone, a highly restricted area in northern Ukraine that surrounds the site of the 1986 nuclear disaster, has become a tourist hotspot. Each morning, tour buses queue at the entry checkpoint where a souvenir shop plastered with nuclear warning symbols peddles neon keyrings and radiation suits. The guides’ t-shirts read: “Follow me and you will survive”. In fact, the dangers are minimal. Along their tightly demarcated routes, these visitors will be exposed to less radiation than during a routine x-ray.

Existing in the shadows of this highly commodified industry is the secretive subculture of the “stalkers”: mostly young Ukrainian men who sneak into the Zone illegally to explore the vast wilderness on their own terms. The name originates from the 1972 Russian science fiction novel Roadside Picnic. Written by brothers Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, it tells the story of contaminated “zones” created on Earth by aliens, in which rogue stalkers roam, hoping to recover valuable alien technology. The book inspired Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 cult-classic film Stalker.

Beyond youthful rebellion, the motivations of the modern stalkers are complex, and speak to the national trauma that resulted from a tragedy whose effects will be felt for generations. And now there is another side to the practice. Enterprising stalkers have started offering their own “illegal tours” to travellers seeking a less restricted (and therefore more dangerous) experience of the Exclusion Zone. I joined one such tour in an effort to discover why visitors might chose a stalker over an official guide. Can a subculture that is so tied to deep wells of personal and national loss really offer something of value to an outsider?

Accompanying me on my journey into the Zone are two Americans, Bradley Garrett and Steve Doe (not his real name), and a Brit, Darmon Richter. Garrett and Richter are renowned urban explorers; the former’s passion for adventure has earned him a PhD, a column for The Guardian, and criminal convictions in four countries, while the latter himself runs tours of post-socialist ruins. We meet in a bar, awaiting our stalker, Kirill Stepanets. Having first visited Chernobyl at the age of 21, Kirill has completed over 100 illegal trips to the Zone. When he arrives, he is tall and fair, with long stubble and a round face. His frameless glasses bounce in unison with jovial, shifting facial expressions. He is not the stoic, battle-scarred individual I had pictured.

Before long, we are driving through a town close to the Zone’s perimeter. “They will bring us here if we get caught,” Kirill jokes, doing little to calm my nerves. Nobody knows the exact implications of getting caught for a foreigner; the least we can expect is a jail cell.

The van delivers us to the head of a dark, sandy trail. Neon-green fireflies pulse gently around us as we creep past a police checkpoint. Soon we are wading through the waist-deep Uzh river that forms the Zone’s southern border, bags held above our heads. Once on the other bank, Kirill turns and grins: “Turn your lights on. Nobody can see us now.”

Our destination for the night is a small village left uninhabited for 32 years — bar the occasional stalker. The road has long disappeared below the forest floor; bungalows emerge as angular shadows from between the trees, like witch’s cabins in a cartoon nightmare. Foliage reaches into open windows and paint crinkles away from brickwork. Most of the roofs are sunken or collapsed, having succumbed to the weight of three decades of decay.

The house we enter is in better shape, although inside there is little sign of its former residents. Gone are their possessions, furniture, radiators, even wiring. A thick layer of chalky dust covers the floors. “It’s not radioactive,” Kirill says, walking between the rooms, “but it is dirty.”

My thoughts turn again to Roadside Picnic. Parallels are easily drawn between Chernobyl stalkers and those from the novel, not least their high tolerance of risk. One such risk is ingesting strontium-90, a radioactive particle found in soil, water, and wild food from the Zone. The body absorbs strontium as calcium, potentially leading to bone cancer decades later. Despite this, videos of stalkers consuming water and fruit from the Zone emerge regularly. In our case, guides from official tours would hide supply caches for us to recover. But this, as we were to discover, brought its own risks.

Darmon and I wait in silence between the trees, not knowing what has become of Kirill, Steve, and Bradley. The glare of torches breaks through the trees. My heart thumps so loudly I’m afraid it will give us away. I lie against the forest floor, paranoid that my every breath is bringing strontium particles drifting into my mouth.

“Guys?” sounds a familiar voice. It is them, and they have the cache.

“The idiot left it five metres from a checkpoint with a fucking dog!” Kirill tells us. “Took me four goes to crawl close enough. The guard came out, but we ran.”

We unpack the supplies and I ask Kirill if he is OK. “Better than all the people in the world!” he responds, slicing his camping knife into a salami.

Steve is more concerned. “Won’t the guard come looking for us?”

Kirill gives a dismissive wave of his hand. “He is too lazy. He won’t leave his comfortable chair.”

As the adrenaline wears off, I struggle to remember a time I had felt more tense, or more exhilarated. This combination, of course, is part of the attraction of stalking: unlike the theatre of official tours, here the stakes are real. You evade capture, or you go to jail. You have bottled water, or you roll the strontium dice.

The following day, we hike through vast meadows and wild forests. Despite being described as a “dead zone”, every corner is brimming with life. Eagles swoop low, deer run freely, wild boar grunt, and insects bustle. In the midst of this natural utopia, the crippled artifacts of humanity reveal themselves: a road sign, a field gate, a crumbling storehouse. Reminders that, once upon a time, this land was part of the empire of the Soviet Union.

Kirill wanders ahead, spinning and jabbing a stick he acquired to clear a path through the spiderwebs. “Pow, yeah!” He seems oblivious to the world around him. He stops next to a tree with huge red apples hanging from it, picks one and bites into it. “Delicious!”

It occurs to me that Kirill was born four years after the disaster and just one year before the USSR collapsed. All he knows of that state is the turmoil that followed. But here in the Zone, he can step back into Ukraine’s not-so-distant past and recover a small part of what was lost. Walking freely among the poisoned ruins of the great empire that shaped his world, perhaps the trauma of its collapse is easier to comprehend.

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, lax security and endemic corruption have meant the Zone is easy to penetrate. Looters, metal thieves, poachers, and loggers are commonplace. There are even rumours of criminals extracting plutonium, or burying bodies in the Red Forest — a highly contaminated area of woodland along the road to Pripyat, Chernobyl’s “dead city”. The soil there is so contaminated that even the police are not allowed to intervene, making it the perfect place to conceal something you never want discovered.

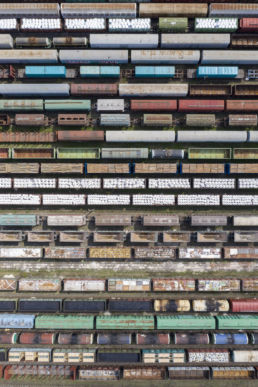

We wait until dark before setting off towards Pripyat. “The road is long, dangerous, and very boring,” Kirill tells us. “Stay quiet and in line. My last group moved like cattle.” He motions his hand haphazardly.

A sliver of moon illuminates the tarmac. Above me, glistening, unpolluted stars keep my mind from the fact that, once again, I am out of water just when I need it most. We round a corner and Kirill stops. In the distance, a dim light dances gently by the road.

“A torch?” Bradley asks.

“Maybe illegal workers,” Kirill says. “We must be careful.”

He directs us onto a railway track which runs parallel to the road, separated by 20 metres of radioactive foliage. We creep from one sleeper to the next. In the darkness the slabs of wood appear to shift beneath my feet. I miss one; the crunch of stones shatters the silence like a crack of lightning.

As we pass the dancing light, I see what appears to be a tent beside the track. The others look elsewhere and see something different. “Two men in white Hazmat suits, digging,” Steve hisses after we pass. An official tour guide would later report back to me that, at the spot I described, he saw freshly turned earth, about the size of a grave.

Trudging through the forest, we approach Pripyat, exhausted and thirsty. At a clearing we turn off our lights. My eyes adjust to the familiar darkness and I see tarmac at my feet. But there is something else, too. I can feel it. As I lift my gaze the sight sends a shiver through my depleted body. All around us, towering shadows reach high above the treeline. Like 15-storey headstones, the city’s apartment blocks stand silent, frozen, and hopeless. It is mesmerising. My body ceases complaining. This is something that no book, photo, film can convey: a foreboding sense of the unimaginable tragedy that unfolded here.

Under the next morning’s light, we explore the ruined buildings that have made Pripyat such a popular tourist attraction. Inside, children’s dolls and gas masks lay arranged in photogenic still-lives, elaborate fictions constructed for dramatic effect — a reminder that most Chernobyl tourism is about Instagram likes, not history.

At the corner of an overgrown junction on the outskirts of the city, we pass a large concrete sign with some sarcastic stalker graffiti: “Tours for profit: we make money from tragedy.” Kirill laughs. “Stalkers are hypocrites — they would make money if they could.”

Later, from the highest rooftop in Pripyat, we watch lightning illuminate the evening sky. Angry forks of electricity appear to strike the giant metallic dome of the protective “sarcophagus” that now houses the defunct reactor. In the distance, a dog barks: a sign of more stalkers? “There are maybe 50 stalkers in Pripyat right now,” Kirill tells us.

Tomorrow we will return to the real world, smuggled out in a worker’s jeep. For now, there some is time to reflect. In the last four days, I’ve walked 70 kilometres and endured discomfort and adrenaline-induced anxiety. I’ve slept six hours in total, reeled with radiation paranoia and faced the prospect of disaster. At times the tragic surroundings have been profoundly affecting. Now, my body aches more deeply than ever. Yet in spite of all this, I feel good. My mind is quiet and alert. Is this my prize for enduring the risks?

The idea that Ukrainians are drawn to stalking as a form of catharsis is logical. By occupying the Zone, they redefine a wound in the national psyche. It becomes at once a museum, a nature reserve, and a haven from the turbulent country outside. As the nation struggles with chronic uncertainty, life in the Zone remains the very antithesis of instability. Even as an outsider, these motivations remain pertinent. Stalking delivers an insight into a historical event of chilling relevance in a way that an official tour cannot. Meanwhile, the sheer physical rewards of risk and survival combine, in a fashion, to deliver an unlikely meditative escape.

Given this varied appeal, it is possible that stalking will quickly become a victim of its own success. What happens when the popularity of these tours leads to a crackdown? Kirill is unconcerned: “The police have no money. Anyway, more stalkers mean more people for them to catch before me.”

The acute dangers involved rather than the police will likely prevent illegal tours from developing too far. Even surviving a trip intact is not guarantee of safe passage: it will be decades before I know whether I accidentally ingested strontium-90.

Nevertheless, just as the characters of Tarkovsky and the Strugatskys are drawn back to their treacherous alien zones, it is easy to see how, for some — even outsiders — stalking can become an obsession. Alongside the rich academic attraction, stalking provides a unique way to satisfy a deep thirst for adventure that has, in the modern world, become difficult to quench. As I write these words safely cocooned at home, the thought of returning to that dark, uncomfortable, mysterious, exhilarating existence is undeniably alluring.

“It’s like during war,” Kirill told me. “When a soldier returns home, he hates normal life. He just wants to go back.”

This article was originally published on The Calvert Journal on January 8th 2019

In the Presence of Absence

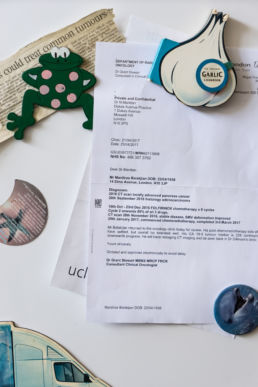

In May of 2017, I took my terminally ill father to Armenia, his cultural homeland and a place in which he had never set foot. As we explored Armenia’s majestic landscapes and ancient historical sites, there was an unspoken, yet palpable sense that this was our last journey together.

He would pass away just two months after our return. In documenting the final months of my father’s life in this way, this series explores how knowledge of our own mortality, and later the presence of absence itself, affects our perception of the world around us.

This series was shortlisted for the Hellerau Photography Awards 2018, held in Dresden, Germany.

Hong Kong - Between the Shadows

Hong Kong is one of the most densely populated places on the planet. Standing on the city streets, it is all but impossible to be alone. Yet, hiding in the shadows of this chaos are countless moments of serene isolation.

Inside the Nightly Market that Feeds Hanoi

This series was published on Fodor’s in October 2018.

Hanoi is well known for its vibrant, busy streets that provide a plethora of ways to stimulate the adventurous traveler’s senses. Yet, while most of the city’s visitors are safely tucked up in bed, an extravaganza like no other is developing under the cover of night. From 2 a.m. onwards, seven days a week, Hanoi’s restaurateurs, food retailers and street vendors flock to the sprawling Long Bien market complex. Over 1,200 stalls, lockups, and trucks sell wholesale fruit, vegetables, and fish by the crate. By 5 am, as the sun breaks over the horizon, the market is complete pandemonium. Come midday, however, the crowds have dispersed and peace has returned to the area. The daily cycle of boom and bust allows visitors who are willing to skip some shut-eye to witness the compelling, truly Vietnamese story of the Long Bien market.